![]()

Bring the Right People Together

Product discovery is a team sport. You should therefore involve the right people in the discovery work and secure enough of their time. I find it helpful to form a product discovery team that consists of:

- Development team members: user experience (UX) designer, developer, tester;

- Key stakeholders, for example, people from marketing, sales, and support;

- A ScrumMaster or agile coach.

Involving others in the discovery work allows you to leverage their knowledge and expertise, builds rapport, and creates support for key product decisions including the selection of a specific market segment and stand-out features.

A UX designer, for example, might help you observe and interview users; and a developer and tester might advise you on technical feasibility, identify technical risks, and build prototypes; a sales rep might get you in touch with target users and help you with competitor research; a ScrumMaster might facilitate collaboration and advise on process issues—for instance, which process and tools should be best used to visualize and track the discovery work. (I prefer to use a Kanban-based process and a Kanban board, as I discuss in my book Strategize in more detail.)

Focus on Problem Validation, not Solution Building

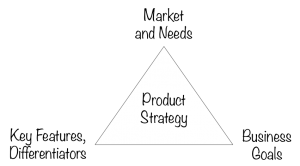

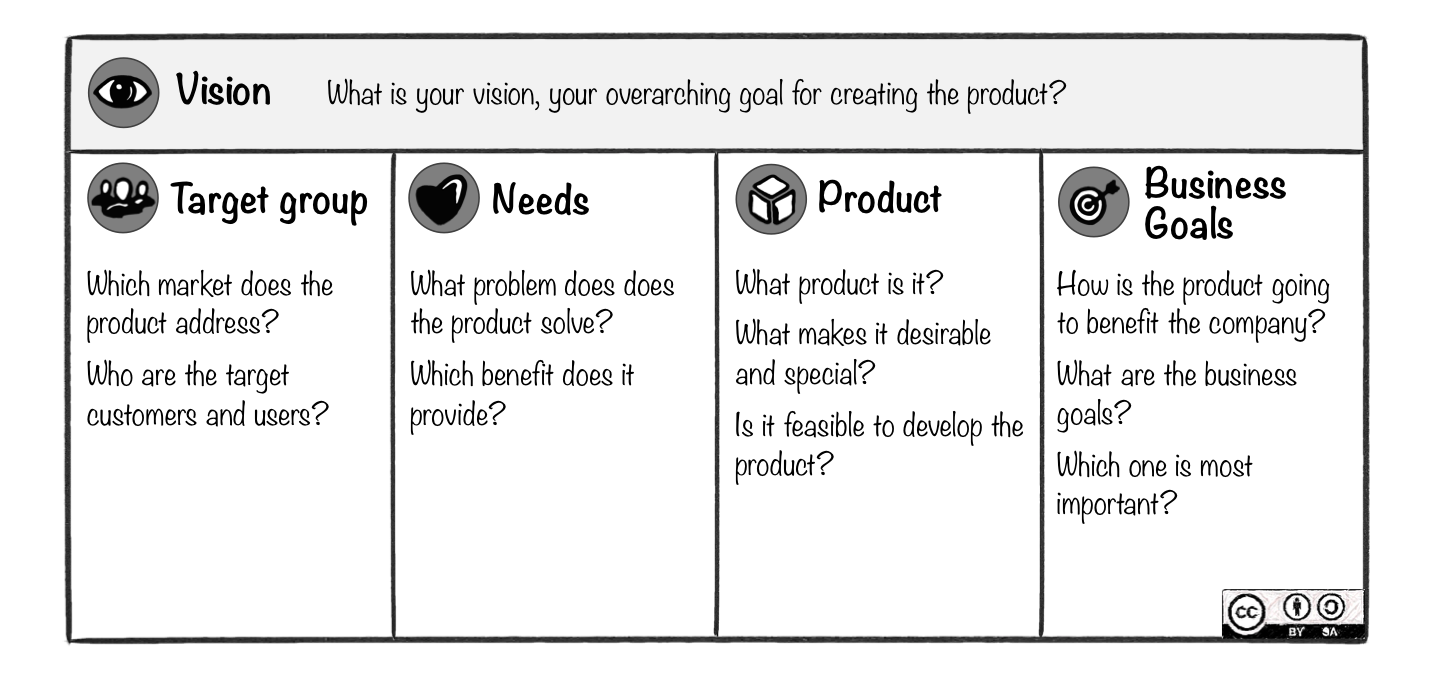

Your product discovery work should focus on nailing the value proposition, target group, business goals, business model, and stand-out features of the product—not on writing user stories, designing the user interface, or building the actual solution. Your goal should be to mitigate the risk of building a product nobody wants and needs, not to figure out the product details.

Having said that, it’s ok to address key UX and technology risks and evaluate important user interaction and architecture options as part of the discovery work. But the bulk of the UX design, user story writing, and technology work should be done after you have successfully validated the problem.

To get your focus right, consider using a tool like my Product Vision Board to capture your idea, and identify assumptions and risks.

Do Just-Enough Product Discovery Work

Minimise the amount of time you spend on product discovery in order to accelerate time-to-market. You should aim to get a good enough product out as fast as possible, and then adapt it to the market feedback. There is no way to guarantee that the product strategy and business model are spot on, and that the new product or next version will be a success.

But don’t rush the necessary work, and resist the temptation to jump start building the actual product. Explore the key assumptions and risks in your product strategy and business model by systematically testing and addressing them in an iterative fashion using, for example, observations, interviews, surveys, and prototypes.

If you can’t confidently state why people are going to use your product, who those individuals are, what makes your product stand out from the crowd, and why it’s worthwhile for your business to develop and provide the product, then you are not in a position to build the actual solution. Instead, continue the discovery work (persevere or pivot), or stop and move on to another product idea.

Talk to the Users

With all the product discovery work that needs to happen, it can be easy to lose sight of the most important success factor—the people who are going to use the product. There is no point in coming up with a smart business model and sophisticated user interactions, if you don’t know who the users are, what they may be struggling with, and what works well for them, and what doesn’t. If the users don’t need and like your product, you will find it hard to monetise it and achieve product success.

Therefore, get out of the building (as Steve Blank says) and meet target users face-to-face as part of the discovery work. I know that’s not always easy. But to succeed with product discovery, I find it paramount that you—the person in charge of the product—carry out user research yourself and develop a deep understanding of the user needs.

When talking to users, take a genuine interest in the people you meet. Have an open mind and let go of preconceived notions about the problem you think the users have or the solution you believe they need. This allows you to discover what people really want and need thereby maximising the chances of creating a successful product.

Don’t Handoff Product Discovery Work

The people involved in product discovery should also participate in building the actual solution. The UX designer, developer, tester should work on the development team. The stakeholders should regularly attend product strategy and roadmap reviews, as well as sprint review meetings. This speeds up the product innovation process, creates a smooth transition from discovery to delivery activities, and mitigates the risk of loss of knowledge.

Handing off the discovery work is ineffective and wasteful: It requires detailing the knowledge acquired in form reports and other artefacts. This is time-consuming, and it is likely to lead to misunderstandings and loss of knowledge—it is hard to precisely capture the discovery learnings, and written information is open to misinterpretation.

Therefore, refrain from using separate discovery and delivery teams. I find it is usually better to involve more people from the development team rather than opting for two distinct teams. Remember that quickly learning what to do (and what not) and quickly delivering the right solution are more important to product success than efficiency and saving money—at least in the early life cycle stages.

Consider Timeboxing the Product Discovery Activities

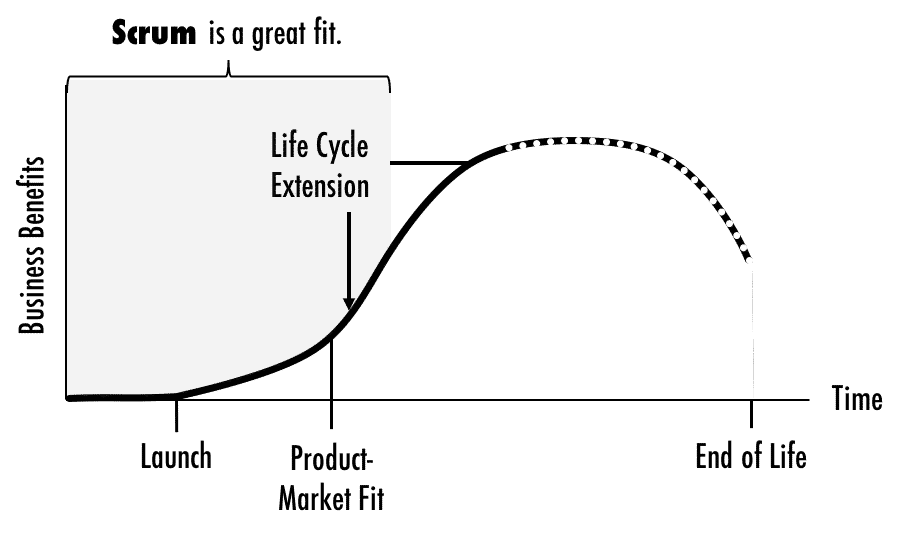

Knowing upfront how much time and effort will be required to carry out the necessary discovery work is tricky. New risks and work items often emerge as part of the validation work. Luckily, there is a straightforward solution: timebox your product discovery work. This technique is particularly useful when you work on a new product or when you make a bigger change to an existing one, for example, to take the product to a new market in order to extend its life cycle.

A time box is a fixed period of time, such as one week, that cannot be extended. At the end of the time box, the work stops, and you reflect on what has been achieved. If the work has not been completed, and your product strategy and business model still contain significant risks, you have two options: add another time box—and possibly pivot—or stop the work.

Consider holding weekly review meetings that involve the people carrying out the validation work as well as the management sponsor. Use the meetings to reflect on the risks that are being addressed and the learnings that you have achieved; consider the risks that still exist in your product strategy and business model; and decide if and how to continue.

Don’t Limit Product Discovery to New Products

While the traditional usage of the term suggests that product discovery is the first stage in a new-product development process (see Cooper’s Stage-Gate![™]() process), it would be a mistake to limit product discovery to new products.

process), it would be a mistake to limit product discovery to new products.

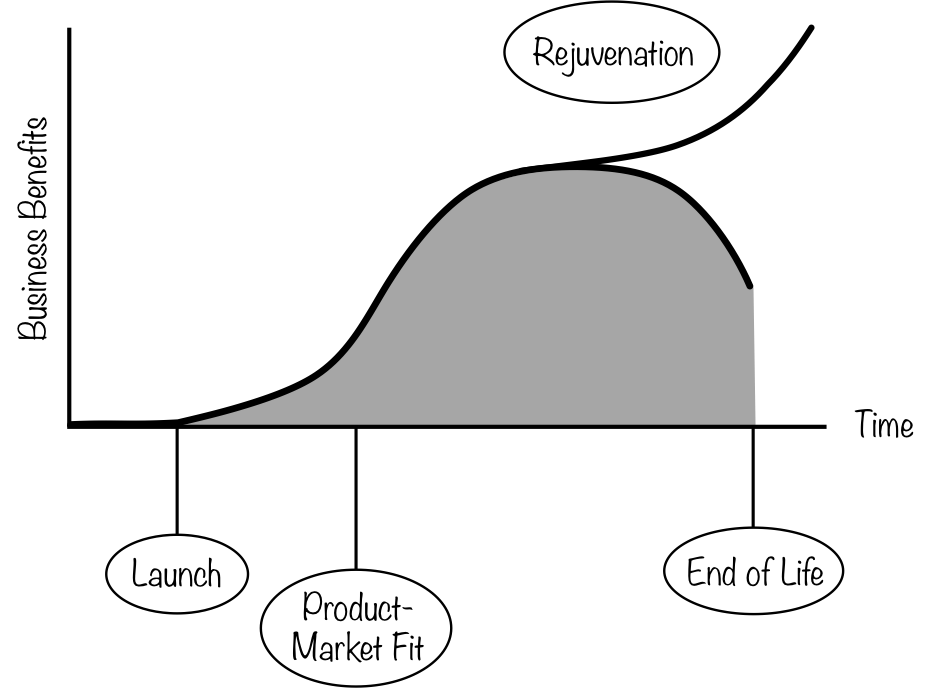

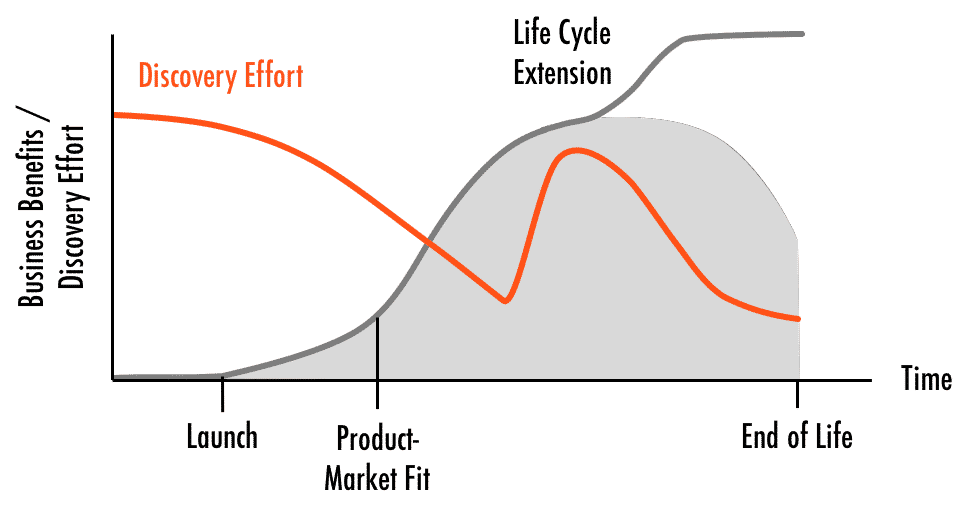

As your product grows and matures, its value proposition, market, stand-out features, and business model will change. To make and keep your product successful, it is paramount that you proactively review and adjust your product strategy, roadmap, and business model. These adjustments sometimes require little or no product discovery work.

But when bigger changes are required, such as, taking your product to a new market or adding features and redesigning the user experience to sustain growth, you’ll likely have to carry out specific discovery work, as the picture below shows. If that’s the case, then I recommend anticipating the work and stating it on your product roadmap.

![Product discovery effort and product life cycle with extension]()

Modern product discovery is hence best understood as a set of activities rather than a clear-cut phase that is separated by a milestone or gate from building the actual solution.

The post Product Discovery Tips appeared first on Roman Pichler.

To prevent such a portfolio, invest 25% of your budget in brand-new products and question marks, and ensure that the teams have the right environment to quickly experiment, fail, and learn.

To prevent such a portfolio, invest 25% of your budget in brand-new products and question marks, and ensure that the teams have the right environment to quickly experiment, fail, and learn.

Please note that the line representing the discovery effort is in the picture above is only a rough approximation. In reality, the discovery effort may be higher or lower, and it may fall later or sooner.

Please note that the line representing the discovery effort is in the picture above is only a rough approximation. In reality, the discovery effort may be higher or lower, and it may fall later or sooner.

process), it would be a mistake to limit product discovery to new products.

process), it would be a mistake to limit product discovery to new products.

The MVP is called minimum, as you should spend as little time and effort to create it as possible. But this does not mean that it has to be quick and dirty. But try to keep it as small as possible to accelerate learning and avoid the possibility of wasting time and money, as your idea may turn out to be wrong!

The MVP is called minimum, as you should spend as little time and effort to create it as possible. But this does not mean that it has to be quick and dirty. But try to keep it as small as possible to accelerate learning and avoid the possibility of wasting time and money, as your idea may turn out to be wrong!

Note that a minimal marketable product differs from a viable one: It is complete enough to be ready for general release, as indicated by the gift wrapping in the picture above. What’s more, launch preparation activities have to take place for an MMP, for instance, creating advertising campaigns, or gaining certification. Some of your MVPs are likely to be throwaway prototypes that only serve to acquire the necessary knowledge; others are reusable product increments that morph into a marketable product.

Note that a minimal marketable product differs from a viable one: It is complete enough to be ready for general release, as indicated by the gift wrapping in the picture above. What’s more, launch preparation activities have to take place for an MMP, for instance, creating advertising campaigns, or gaining certification. Some of your MVPs are likely to be throwaway prototypes that only serve to acquire the necessary knowledge; others are reusable product increments that morph into a marketable product.